The adornment of silence

secrecy and symbolic power in American freemasonry

by Hugh B. Urban

Ohio State University

Introduction

The secret operates as an adorning possession. . . . This

involves the contradiction that what recedes before the consciousness of . . .

others and is hidden from them is emphasized in their consciousness; that one

should appear as a noteworthy person through what one conceals (Simmel: 337).

I will always hail, ever conceal, and never reveal (Pike 1871: 63).

[1] It is surely one of the most striking paradoxes

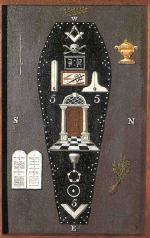

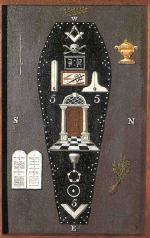

in the history of American religion that the period of the late nineteenth

century - the same period which witnessed an intense acceleration of

technological progress, social and economic growth, industrialization and

urbanization - also witnessed the greatest flowering of the esoteric rituals and

secret traditions of Freemasonry. This was an era permeated by what some have

called a "general mania" of clubs, fraternal organizations, secret societies,

and above all the Masonic Lodge. In the years between 1879 and 1925, in fact,

membership in the Lodges suddenly rose from 550,000 to over three million (Dumenil:

xii; Kauffman: 8f; Clawson). Even as the mainstream Protestant churches were

attempting to address the problems of an increasingly urbanized, industrialized,

and multi-racial society, the Lodges were attracting white, middle class native

males in unprecedented numbers. The widespread presence of the Masonic lodges in

the late nineteenth century, and above all, the popularity of the most esoteric

Lodges like the Scottish Rite, present us with a series of apparent

contradictions: an ideal of democracy and liberty side by side with elitism and

authoritarianism; and a rhetoric of brotherhood and universal humanity side by

side with elaborate hierarchies of exclusion (Carnes 1989; Dumenil).

|

|

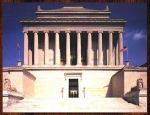

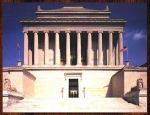

Figure 1

Albert Pike as Grand Commander, ca. 1875 (Fox) |

[2] Known as the "Moses" of American Freemasonry,

Albert Pike (figure 1) stands out as perhaps the clearest single embodiment of

the series of paradoxes which pervade the nineteenth century Lodge. A man of

remarkable boldness and tremendous egotism, Pike was, in his youth, one of the

greatest adventurers in the American Southwest. In his maturity, he served as

Brigadier General in the Confederate Forces during the Civil War. Yet after

losing his entire fortune and reputation due to a humiliating scandal, Pike

retired into the esoteric traditions of Scottish Rite Masonry. If he had lost

his previous economic wealth and status, it would seem that he recovered a new

kind of status, power and prestige as the greatest scholar of the Scottish Rite

and the most respected authority on the innermost secrets and highest degrees of

the Brotherhood.

[3] Various scholars have offered possible

interpretations for the enigmatic role of American Freemasonry. As early as

Toqueville, for example, it was suggested that the obsession with secret

fraternities was the consequence of a democratic society without fixed

hierarchies: "In a nation devoid of established hierarchies and traditional

protections, the citizens sought strength through association" (129; cf.

Kauffman: 8). Others like Mervyn Jones and Brian Greenberg have pointed to the

role the Lodges played in late nineteenth century business and capitalism, as a

kind of "unofficial guild of businessmen" amidst modern industrialized society

(Jones: 177). And still others like Lynn Dumenil argue for the sociological

function of American Masonry, which served as a spiritual oasis in a rapidly

changing and increasingly heterogeneous world. By separating men from the

outside world, placing them securely amongst the brothers of the lodge, the

Lodge reinforced the traditional values of middle-class white Protestant men (Dumenil:

32-42; cf. Clawson 1984: 6ff).

[4] Unfortunately, although Dumenil and others have

provided useful insights into the social role of Masonry, few have made serious

efforts to understand the enormous role of secrecy, occult symbolism and ritual

in the Lodges. In other words, why did these middle class men take such delight

in arcane secrets and esoteric ceremonies, rather than joining a more secular

fraternal group? One of the few scholars to examine the role of secret ritual in

the Lodges is Mark Carnes, who combines psychological and sociological theory to

look at gender symbolism in Masonic initiation. During a period in which

mainline Protestant churches were increasingly dominated by women, he argues,

the secret initiation of the Lodge offered a means of achieving the difficult

transition from the feminine world of domesticity to the masculine world of the

workplace. The aim of fraternal ritual was, in short, to "provide solace and

psychological guidance during young men's passage to manhood in Victorian

America" (1989: 14; cf.1996: 72f).

[5] While not denying the value of each of these

interpretations on a limited level, I will suggest a new approach to the problem

of nineteenth century Masonry, and more importantly, to the problem of secrecy

in the history of religions as a whole. Secrecy, I will argue, is best

understood not in terms of its substance or content, but rather in terms of its

form and the ways in which secrets are concealed and exchanged.

Here I will adapt and modify some of the early insights of Georg Simmel, and his

key notion of secrecy as an "adorning possession." Rather than a simple

mask for some alleged hidden content, secrecy, Simmel argues, is a sociological

form which adorns the owner of concealed knowledge with the mark of social

distinction or status. Like fine clothing or jewelry, secrecy simultaneously

conceals even as it reveals, at once hiding certain aspects of its

wearer from view and surrounding him with an aura of mystery, awe and power

(337ff). Secrecy thus functions much like Pierre Bourdieu's notion of "symbolic

capital" - as a rare, scarce resource or valuable commodity, which confers a

special kind of prestige and so determines one's status within a given hierarchy

of power (1977a, 1981).

[6] It is precisely this kind of adornment or

capital, I submit, that attracted Pike and so many others to the arcane

mysteries of the Lodge. Although Masonry, like other esoteric organizations, has

frequently been attacked as a subversive, rebellious, or "counter-cultural"

phenomenon (Tiryakian; Roszak), more recent scholarship has shown that the

Lodges were predominantly conservative, respectable, and elitist organizations.

In contrast to many working class fraternal groups, the Masonic orders

reinforced traditional values, conferred status and cemented business relations,

primarily among white, native, middle and upper class males (Dumenil: 89ff). As

I will argue, Pike and others turned to the secret mysteries of the Lodge in

large part as a means of reinforcing their own symbolic capital. It helped these

white males to maintain their traditional status amidst the rapidly changing

world of post-Civil War America, in the face of tremendous economic growth,

racial integration, feminism, and other forces which threatened their long held

privileges. Masonry offered a means of preserving the cherished American ideals

of democracy and freedom, while at the same time maintaining a clear form of

elitism and exclusivism. At the same time that it constructed an elaborate

hierarchy of advancements, ostensibly based on "merit" and moral goodness, it

also masked and re-coded deeper differences of wealth, class, sex, and race.

[7] After a theoretical discussion of the problem of

secrecy, I will recount Pike's life and his role in late nineteenth century

Masonry. I will then examine three main strategies employed by Pike and his

fellow Masons in their quest for symbolic capital: first, the creation of a new

social space, which is ostensibly based on egalitarianism and meritocracy, but

which in fact reproduces the status of a small elite; second, the preoccupation

with esoteric symbolism, which creates a body of rare and valuable knowledge

that can be exchanged as a source of symbolic capital; and third, the

construction of an elaborate hierarchy of degrees, which offers a ladder of

upward mobility and ever-increasing "distinction."

The Adornment of Silence: Secrecy and Symbolic Capital

Among children, pride and bragging are often based on a child's

being able to say to the other: I know something you don't know...This jealousy

of the knowledge about facts hidden to others is sown in all contexts from the

smallest to the largest. . . . The secret gives one a position of exception. . .

. All superior persons . . . have something mysterious. From secrecy . . . grows

the error according to which everything mysterious is something important and

essential (Simmel: 332-33).

All men desire distinction, and feel the need of some ennobling

object in life (Pike 1871: 349).

[8] The past several years have witnessed a

remarkable proliferation of interest in the topics of secrecy and esotericism.

Not only in a variety of academic disciplines, but also in popular

entertainment, cinema, media, or novels such as Foucault's Pendulum (and

even, now, on the Internet), there appears to be a growing

fascination with the tantalizing regions of the unknown and the occult. Yet

perhaps rather fittingly, despite this growing interest in the topic, the

subject of secrecy remains poorly understood and theoretically confused in the

academic community. Among historians of religions, such as Mircea Eliade and

Kees Bolle, the study of secrecy has remained disappointingly general,

universalistic and largely divorced from social and historical context. Even

Antoine Faivre's extensive work on Western esotericism takes virtually no

account of the very real social and political contexts in which esoteric

traditions emerge, and within which they are inextricably intertwined (see Urban

1998, in press).

[9] This is not the place to enter into a full

discussion of all the various theoretical approaches - sociological,

psychological, political, literary, etc. - that have been applied to the study

of secrecy. Here I will trust the lead of Beryl Bellman, T.M. Luhrmann, and

others who have critically evaluated the diverse approaches, pointing out the

problems and weaknesses of each. As Bellman suggests, most past sociological

approaches have been hampered by a persistent problem: namely, to define

"secrecy" primarily in terms of a hidden "content", and then to construct

various typologies based on the kind of content or on the effects of revealing

secrets (1-2). Even as early as 1906, Simmel's classic study had pointed out the

crucial distinction between the form and the content of secrecy:

for secrecy is a "sociological form that stands in neutrality above the value

functions of its contents" (331). Yet, Bellman argues, most studies of secrecy

have ignored this distinction, and have instead remained satisfied with

classifying the various contents or effects of secret information. On the one

hand, scholars as diverse as Norman MacKenzie, E.J. Howsbawm, or Mak Lou Fong,

have generated a wide variety of different, often conflicting, typological

schemes based on the content of secrecy. On the other hand, there are those like

Edward Shils, in his classic study of McCarthyism and the dread of Communism,

who have examined the effects of exposing concealed information (22ff). However,

neither of these approaches has proven particularly useful in understanding the

more concrete role of secrecy in social relations; instead, Bellman suggests,

they have contributed to a general confusion in the academic study of secrecy

(1; see Urban 1998, in press).

|

|

Figure 2

Scottish Rite Double-headed Eagle (Fox) |

|

|

Figure 3

Scottish Rite Jewel Belonging to Albert Pike (Fox) |

|

|

Figure 4

Regalia of the 31st Degree (Fox) |

|

|

Figure 5

Regalia of the 32nd Degree (Fox) |

|

|

Figure 6

Regalia of the 33rd Degree (Fox) |

|

|

Figure 7

Costumed Scottish Rite Degree Team (Fox) |

[10] For my own part, I wish to suggest a new

approach to the problem of secrecy by returning to some of Simmel's original

insights and combining them with more recent insights of Bourdieu and Michel

Foucault: it is more fruitful, I submit, to turn the focus of our analysis away

from the content of secrecy and instead toward the forms and the

strategies through which secret information is concealed, revealed, and

exchanged. Here I wish to undertake a "theoretical shift," similar to the series

of shifts undertaken by Foucault in his study of power and sexuality. In his

investigation of the question of power, Foucault realized that he needed to turn

from the study of "power" as an oppressive, substantial force, imposed from the

"top down "in the political hierarchy, to a study of the strategies

through which power is manifested. Power thus appears as a far more subtle,

complex, and plural phenomenon, as a productive rather than an oppressive force,

which is radiated from multiple points at all levels of the social organism. So

too, I would suggest that we undertake a theoretical shift away from the

"secret" as simply a hidden content, and instead investigate the strategies or

"games of truth," through which the complex "effect" of secrecy is constructed.

That is to say, how is a given body of information endowed with the mystery,

awe, power, and prized value of a "secret?" Under what circumstances, in what

contexts, and through what relations of power is it exchanged? How does

possession of that secret information affect the status and prestige of the "one

who knows"? As Bellman has similarly argued in his work on the Poro society of

Liberia:

[S]ecrets cannot be characterized either by the contents of the

concealed message or by the consequences . . . they are understood by the way

concealed information is withheld, restricted . . . and exposed. The practice of

secrecy involves a do-not-talk-it proscription . . . that is contradicted by the

fact that secrecy is . . . a sociological form . . . constituted by the very

procedures whereby secrets are communicated (144; cf. Tefft: 321).

[11] As I wish to define it, secrecy is best

understood as a social form, a strategy aimed at the effect of "adornment." The

concept of secrecy as adornment, I submit, remains one of the most provocative,

most useful, and also hitherto most ignored aspects of Georg Simmel's classic

early study on secrecy, and one in most need of further development. As I wish

to define it, secrecy or the controlled circulation of valued information serves

to transform knowledge into something rare, a scare resource. Like precious

jewelry (figures 2 and 3) or expensive clothing (figures 4, 5, 6, and 7), it is

a covering, something which conceals or obscures aspects of the

physical person; but it is also an ornament, something which accentuates

the person, and so serves as a mark of distinction and prestige. The secret,

like a piece of fine jewelry or clothing, "radiates" a kind of aura of good

taste, honor, and status which also masks the more real material and economic

basis of its existence:

Adornment intensifies or enlarges the impression of the

personality by operating as a sort of radiation emanating from it. . . . The

radiations of adornment, the sensuous attention it provokes, supply the

personality with such an enlargement of its sphere: the personality, so to speak

is more when it is adorned (339-40).

[I]n the adorned body we possess more; if we have the adorned

body at our disposal, we are masters over more and nobler things. . . .

Bodily adornment becomes private property above all: it expands the ego and

enlarges the sphere around us . . . which consists in the pleasure and the

attention of our environment (344, my emphasis).

Adornment is thus a critical part of the larger process of social

transformation: it is that mystifying process which turns ordinary material

wealth (the possession of jewelry or clothing) into social wealth (the

possession of prestige, dignity or respect): "Adornment is the means by which

social power is transformed into visible, personal excellence" (343). So too,

the "adornment of silence" that we find in secrecy likewise serves to transform

the possession of certain valued knowledge into the possession of status and

superiority.

[12] Here I would like to combine Simmel's early

notion of secrecy as adornment with Pierre Bourdieu's more recent concept of

symbolic capital (1986; cf. Calhoun). Extending Marx's definition of the term,

Bourdieu defines capital as including not only economic wealth, but also the

nonmaterial resources of status, prestige, valued knowledge, and privileged

relationships. It refers in short to "all goods, material and symbolic that

present themselves as rare and worthy of being sought after in a

particular social formation" (1977a: 178; cf. 1981: 118-19). Like economic

capital, however, symbolic capital is not mere wealth which is simply hoarded

and stockpiled; rather, it is a self-reproducing form of wealth - a kind

of "accumulated labor," which gives its owner a form of "credit," or the ability

to appropriate the labor and products of other agents (1986: 252ff). Symbolic

capital is itself the product of a kind of "social alchemy," a process of

misrecognition, through which mere economic capital is transformed and

legitimated in the form of status, class, or distinction. This is the process at

work, for example, in the purchase of an expensive work of art, which confers

the mark of taste upon its owner, or in the investment in a good education,

which bestows cultivation and "cultural capital." As such, the dynamics of the

social field are determined largely by the strategies and maneuvers of agents in

their ongoing competition for these symbolic resources:

Symbolic capital is the product of a struggle in which each

agent is both a ruthless competitor and supreme judge. . . . This capital can

only be defended by means of a permanent struggle to keep up with the group

immediately above . . . and to distinguish oneself from the group below (1981:

123).

[13] In the context of an esoteric organization, two

processes are at work that serve to transform secret knowledge into a kind of

capital. First, the practice of secrecy and the strict guarding of information

transforms knowledge into a scare resource, a good that is "rare and worthy of

being sought after." To use Bourdieu's terms, secrecy involves an extreme form

of the "censorship" which is imposed on all statements within the "market of

symbolic goods." For every individual censors his or her expressions in

anticipation of their reception by the other members of the social field (1977b;

1984: 77). Secrecy, however, is an extreme form of self-censorship - a

deliberate, self-imposed censorship - that occurs in a very specific linguistic

market. Its function is to maximize the scarcity, value, and desirability of a

given piece of knowledge. For "if you seek to create highly valued

information . . . you must arrange worship so that few persons gain access to

these truths" (Barth: 217). Likewise as Luhrmann comments:

Secrecy is about control. It is about the individual possession

of knowledge that others do not have. . . . Secrecy elevates the value of the

thing concealed. That which is hidden grows desirable and seems powerful (161).

All knowledge is a form of property in that it can be

possessed. Knowledge can be given, acquired, even sold . . . like the difference

between private and public property, it is secret knowledge that evokes the

sense of possession most clearly (137).

[14] As Lamont Lindstrom has suggested in his work

on the peoples of Tanna in the South Pacific, secrecy is a central part of the

"conversational economy" which constitutes every social order. The practice of

secrecy serves to transform certain information into something that can be

owned, exchanged, accumulated - "a commodity, something that can be bought and

sold" (xii-xiii). As such, what is important about secrets is not the hidden

meanings they profess to contain, but rather, the complex "economy of exchanges"

or the resale value which secrets have as a commodity of knowledge and power

within a given "information market":

Secrets turn knowledge into property that can be exchanged.

People...swap or sell their secrets and/or their knowledge copyrights for . . .

money and other goods. Marketable information of this sort includes, spells,

medicines, songs, metaphorical words with new meaning. . . . By preserving

pattern of ignorance within the information market, secrecy fuels talk between

people who do not know and those who do (119).

[15] Secondly, once it has been converted into this

kind of scarce resource or valuable commodity, secret knowledge can serve as a

source of "symbolic capital" in Bourdieu's sense of the term, as a form of

status and power which can be accumulated by social actors, and which is

recognized as "legitimate" by others within a given social field. As Simmel

himself had long ago pointed out, "The secret gives one a position of

exception. . . . [A]ll superior persons have something mysterious" (337).

Secret knowledge thereby functions both as a form of both "cultural capital" -

that is, as special information or "legitimate knowledge", which purports to be

the key to inner gnosis - and as a form of "social capital" - that is, a sign of

membership within a specific community, and of hierarchical relationships with

significant others (e.g. between the master who holds esoteric knowledge and the

initiate to whom it is given). Particularly when combined with a series

initiations or a hierarchy of grades, this is, like all capital, a

self-reproducing form of wealth, which grows increasingly more profound and

powerful as one advances in the ranks of esoteric knowledge and ritual degrees.

[16] However, in distinction to most of the forms of

"capital" which Bourdieu discusses, the symbolic goods of the secret society can

only be exchanged behind closed doors, in the esoteric realm of ritual. Secret

knowledge is not valued and exchanged publicly in mainstream society or in the

field of exoteric relations, but solely within the field of the esoteric

society. Hence we might even call it a kind of "black market symbolic capital,"

a form of capital which is valued only in special circumstances outside of

ordinary social transactions. Indeed, in some cases, this knowledge may even be

considered dangerous, threatening, or illegal in the eyes of mainstream society.

This danger, however, only makes it all the more powerful, valuable, and

desirable.

[17] As such, the strategy of secrecy may be

employed for a variety of different social interests. It may be used by the

ruling elite to reinforce a particular social arrangement or hierarchy of power,

but it may also be used by subordinate and marginalized groups to subvert,

challenge, or undermine such hierarchies. In Foucault's words, "silence and

secrecy are a shelter for power, anchoring its prohibitions; but they also

loosen its hold and provide for areas of tolerance" (1978: 101). Unfortunately,

most past literature on secrecy has tended to exaggerate its revolutionary,

subversive, anti-establishment potential (Tiryakian; Hobsbawm). I shall argue,

on the contrary, that secrecy is very often, perhaps even more commonly,

employed by the ruling elites and powerful aristocracies. Tactics of secrecy

very often "work within an established body of tradition which is designed,

not to disrupt order and conformity, but to reinforce it" (Davis: 284).<12>

In Bourdieu's terms, the mystery surrounding secret knowledge is a powerful

expression of that "social alchemy" - that mystification and misrecognition,

which transforms the arbitrary arrangements of society and asymmetrical

relations of power into something that appears "legitimate" or even "natural"

(1977a: 171-97).

The Moses of American Freemasonry: The Life and Works of Albert Pike

The disenfranchised people of the South, robbed of all the

guarantees of the Constitution . . . can find no protection for property,

liberty or life except in secret association (Pike in W. Brown 1997: 440).

[18] Albert Pike (figure 1) stands out as a striking

example of the role of secrecy and esoteric knowledge as a source of symbolic

power. Famed in his youth as an adventurer and "one of the most remarkable

characters in the annals of the Southwest," Pike was revered in his later years

as the greatest authority on Masonry and the foremost proponent of the esoteric

traditions of the Scottish Rite (W. Brown 1997: 417ff; Fox: 89ff). Born in

Boston in 1809, the son of an irreverent, alcoholic cobbler and an extremely

pious, puritanical mother, he was from his youth a man of striking extremes and

contradictions. Although he attended Harvard in 1821, he was soon forced to

leave when he was unable to pay his tuition. Hence, he decided in 1824 to ignore

his mother's wish that he become a minister in order to live an adventurer's

life in the Southwest: he rode on wagon trains , survived snow storms, nearly

froze to death, and fought Indians, all the while exulting in these hardships,

for "he longed to share in the unconstrained life of the noble savage" (Carnes

1989: 136). He was known, moreover, for his wild parties, his skill in seducing

women, and for his tremendous physical and sexual appetites (he is said to have

weighed over 300 pounds in full manhood).

Torn by extremes represented by his irreverent father and pious

mother, Pike initially pursued a quest for manly assertion reflected in frontier

adventures, the pursuit of wealth and military glory, gastronomic and sexual

excess (Carnes 1989: 138).

[19] In 1831, Pike returned to the East, where he

studied law and was admitted to the Bar in 1836. Famed for his heroism in the

Southwest, Pike quickly built up a new reputation among the wealthy society of

Little Rock where he was extremely active and respected in the law, journalism,

and the politics of the day. However, the real turning point in his life did not

occur until he entered the Confederate army during the Civil War, where he held

the rank of Brigadier General, and was placed in command of the Indian

regiments. Pike suddenly became the center of an enormous scandal when the

Indians under his charge killed and mutilated the bodies of the Union soldiers.

At the war's end, Pike was blamed for the incident - by both Union and

Confederate sides - and denounced as the most malevolent of rebels, charged with

disobeying commands and inciting the Indians to revolt. His former wealth and

property were confiscated, and along with them his former status and prestige.

Fleeing civilized humanity, Pike withdrew into the hills of Arkansas and lived

as a hermit in the wilderness. It was not until 1869 that he was publicly

pardoned and allowed to return to society (W. Brown 1997: 443ff).

[20] One of the most controversial and troubling

questions in Pike's life is his possible involvement in another infamous secret

brotherhood which also emerged in the South during the post-war years - the Ku

Klux Klan - and the possible links between the Scottish Rite and the secret

rituals of the Klan. Indeed, many critics have long charged Pike as not only a

member, but even as a founding father of the KKK (see Wade: 58n). As Walter Lee

Brown has shown, there is no concrete evidence that Pike was ever actually a

member or he even had particularly close ties to the Klan. However, given his

political stance, his shattered social and economic position, and his hostility

to the Negro suffrage movement, it is not difficult to imagine that he would

have been deeply sympathetic to such a group: "one might reasonably surmise that

Pike, considering his strong aversion to Negro suffrage and his frustration at

his own political impotence, would not have stood back from the Klan" (1955:

783; cf. Fox: 81-82). As far as is known, Pike only refers to the Klan once in

any printed document, in an editorial to the Memphis Daily Appeal in

1868, where his comments are somewhat critical, but still largely sympathetic to

the cause of the Klan, suggesting that its main problems lie not in its aims,

but in its methods and leadership: "We do not know what the Ku Klux organization

may become. . . . It is quite certain that it will never come to much on its

original plan. It must become quite another thing to be efficient" (cited in W.

Brown 1997: 439). In fact, Pike goes on in the same article to call for

something even greater than the Klan - a great Order of Southern Brotherhood,

uniting all white men of the South in a secret fraternity to defend their

traditional property and power and to work against the Negro cause:

The disenfranchised people of the South, robbed of all the

guarantees of the Constitution . . . can find no protection for property,

liberty or life except in secret association. . . . If it were in our power . .

. we would unite every white man in the South, who is opposed to Negro suffrage,

into one great Order of Southern Brotherhood, with an organization complete,

active, vigorous, in which a few should execute the concentrated will of all,

and whose very existence should be concealed from all but its members. That has

been the resort of the oppressed in all ages (cited in W. Brown 1997: 440).

It was perhaps in his search of such a "resort of the oppressed" that Pike

and many other white men of post-Civil War America turned to the secret

traditions of the Masonic Lodge.

[21] Upon his return to civilization, Pike began to

immerse himself in the study of the most arcane and occult secrets of the

world's esoteric traditions - Kabbalah, Gnosticism, alchemy, Templar traditions,

as well as Indian religions, Zoroastrianism, and the Greek Mysteries.

Withdrawing from his public sphere of military career and law, it seems, Pike

turned inward to the inner realm of mystery, rite, and symbol:

Pike's life was in ruin. He faced charges of inciting the

Indians to revolt, and his property was confiscated by Union officers. He had

squandered his fortune, and his marriage had disintegrated. . . . Pike sought to

refract his experiences through the wisdom of the ancients. . . . He scoured the

classic religious texts...Latin sources, the Zend Avesta and the Indian Vedas,

studying the Cabala and the gnostics (Carnes 1989: 137).

Above all, Pike began to turn to the lore of Freemasonry, which he saw as

both the continuation and culmination of these many ancient esoteric traditions.

Pike is commonly regarded as the single most important figure in the history of

American Masonry, the "Moses and Second Creator" of the Lodge, who "smote the

rock of chaos and brought forth a system of morality more perfect than was ever

built by human hands" (Richardson: 26; cf. Newton: 3; Oxford: 60). Above all,

Pike began to expound the highest mysteries of the tradition, as they were

embodied in the most arcane, most elaborate initiations of the "Scottish Rite."

[22] Pike, I would suggest, is a striking exemplar

of a much broader trend taking place in late nineteenth century America. As

Dumenil, Clawson and others have argued, the sudden popularity of the Lodge in

the late nineteenth century was closely related to the rapidly changing social

and economic context of post-Civil War America. "The period from the 1870s to

the 1890s was one of prolonged, intense, bitter class conflict. . . . Yet it

also witnessed the growth of fraternal orders that attracted a membership of

massive proportions" (Clawson 1984: 6-7; cf. Wiebe: 1-75). This was a period

that saw rapid change on all levels - the growth of an increasingly

heterogeneous society, the break up of small town communities, enormous

technological changes, and national corporations which undermined local

businesses. At the same time, the homogeneity of white Protestant society was

shattered by the influx of blacks and immigrants, who did not always share the

values of middle class American culture. As we see throughout Masonic writings

of the late nineteenth century, there were growing fears of "Pandemonium,

confusion, strife" and the destruction of all stable values of traditional

America.

[23] Many upper and middle class males also appear

to have been seeking an alternative to the mainstream Protestant churches of the

late nineteenth century. As Dumenil and others have pointed out, the churches of

the post-Civil War era began to worry increasingly about their lack of influence

over the urban masses (particularly Jewish, Catholic, and non-English speaking

immigrants) who constituted a large sector outside the pale of American

Protestantism (Mead: 134; Carter; Ahlstrom: 763-84). There was a growing effort

among the Churches to attract and accommodate these groups. At the same time, as

a wide range of scholars have shown, the Protestant Churches of the late

nineteenth century were becoming increasingly dominated by women and women's

concerns. During a period in which two-thirds of all Protestants were women, the

Church came to be identified as the "woman's realm," the "private sphere" of

domesticity, children, and morality. For many white, middle and upper class

males, all of this signified that the church had been "emasculated,"

"feminized," and robbed of its traditional "American" (i.e. white, native, male)

values (Hackett: 131; cf. Carnes 1989: 77; Braude; Cott; Sweet).

[24] Amidst this increasingly pluralistic world,

Dumenil suggests, the Masonic Lodge offered a model of a harmonious society,

free from the increasing chaos of the outside world, where white, native

American males still formed a homogenous and well-governed society. The Lodge

provided a vision of traditional values, as well as respectability and prestige,

for many males who felt profoundly threatened by the changes taking place around

them:

The importance of Masonry's commitment to morality and its

promise of respectability can be understood in the context of late nineteenth

century Americans' struggle to maintain their traditional ideology in the face

of an increasingly disordered world (88).

[25] Pike's classic text, Morals and Dogma of the

Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (1871) stands out as the

single most important work of nineteenth century American Masonry. By no means

simply a commentary on a set of arcane rituals, it is very much a political

document, which constantly reminds the Mason of the direct relevance of the

Craft for society and just government. In fact, the first three chapters of the

text contain at least as much discussion of government and nineteenth century

politics as they do an explication of Masonic symbolism; and the entire third

degree of Master seems to be an exhortation to men of public office, warning

against the dangers of political misrule and advocating the virtues of proper

governance (1871: 62-105). Pike's work makes it clear that Freemasonry is

anything but a rebellious or subversive movement (as it has often been accused);

rather, it claims to be the fullest embodiment of true "American" values. The

text is, moreover, filled with powerful criticisms of the social and political

world around him, as well as a call to all good men to join the well-governed

society of the Lodge. Bemoaning the weakness of the men of his time and warning

of the danger of losing their freedom, he observes that "there are certainly

great evils of civilization at this day," that "this nation is in distress,"

that "fraud, falsehood and deceit in national affairs are the signs of

decadence" and that contemporary politics, both in America and in Europe, have

become "selfish and driven by greed." The nation has become "feminine," passive,

emasculated, as "the effete State floats on down the puddled stream of time. . .

. The worm has consumed its strength and it crumbles into oblivion" (1871: 837,

67-68, 83, 33).

[26] For Pike, the Lodge is nothing other than the

ideal society, the model of the perfect, just government - the "Holy Empire."

For the Lodge represents the perfect wedding of the sovereignty and freedom of

the individual with fellowship and equality for all:

Masonry is a march and struggle toward light. For the

individual as well the nation, Light is virtue, manliness, intelligence,

liberty. . . . The freest people, like the freest man, is always in danger of

relapsing into servitude (1871: 32).

From the political point of view there is but a single

principle - the sovereignty of Man over himself. The sovereignty of oneself over

one's self is liberty. . . . The concession which each makes to all is Equality.

. . . The protection of each by all is Fraternity (1871: 43).

As Pike portrays it, Masonry alone remains un-feminized and preserves the

strength and autonomy of the individual: "Masonry, un-emasculated, bore the

banners of Freedom and Equal Rights, in rebellion against tyranny" (1871: 50).

[27] In sum, it is not difficult to understand why

Pike and so many others like him would have been attracted to the rituals of

Masonry in the late nineteenth century: As the image of the ideal "American"

social order, the Lodge was a social space in which white, native, Protestant

males could retain their long held authority and status. However as we will now

see, these ideals could only be reserved for the elite few by excluding the

profane masses outside of the brotherhood, by enshrouding the Lodge in secrecy

and symbolism, and by constructing an elaborate hierarchical system of

promotions and degrees.

The Lodge as a New Social Space: Egalitarianism, Elitism and Meritocracy

A good Mason . . . is said to live upon the level with all men.

Yet Freemasons are by no means Levellers . . . order and subordination are

requisite for the welfare of society (Reverend James Smith in Jacob: 64-65;

my emphasis).

[28] Throughout the Lodges of the late nineteenth

century, we are confronted by a persistent ambivalence and a double-edged

rhetoric. On one hand, the Lodges tirelessly proclaim the virtues of Masonry as

an egalitarian, democratic institution, in which men of all castes and creeds

join together as free equals. But on the other hand, as most every historian of

freemasonry admits, the lodges were predominantly comprised of upper and middle

class, white native males; moreover, they often clearly served to reinforce the

power and privileges of a small elite, while excluding other groups, such as

blacks, immigrants, and lower classes. As we will see, the key to this double

edged logic is the claim that the Lodge represents a form of "meritocracy:" it

is a hierarchical structure based, ostensibly, on the acquisition of virtue and

moral excellence, but which, in fact, serves to mask and recode deeper

forms of elitism, nativism, and racism.

[29] Like most Masonic works, Pike's writings

celebrate the ideals of equality and the brotherhood of all mankind. The Lodge

is hailed as the embodiment of the unity of all mankind and unity of all

religions, which is in fact even older than Christianity, Islam, and other world

religions. "Freemasonry is one faith, one common star around which men of all

tongues assemble" (Whalen: 10). It was, moreover, on precisely this point that

Pike took issue with the Catholic Pope. Whereas the Catholic Church excludes all

who do not belong to its own institutions, the Lodge opens its arms to all sects

and creeds, recognizing that every man is free to choose his own religion: "No

man has any right to interfere with the beliefs of another . . . each man is

absolutely sovereign as to his own belief . . . opening wide its portal it

invites . . . the Protestant, the Catholic, the Jew, and the Moslem" (Allsopp:

263-64). As such, Pike believes that Masonry is not only compatible with, but is

the true fulfillment of, the ideals of democracy and freedom represented by the

American system of government.

[30] Yet despite this apparently liberating

democratic ideal, Pike and his Masonic brethren were generally far from

egalitarian. As Margaret Jacob and others have argued in the case of European

Masonry, the constant rhetoric of egalitarianism, democracy, and meritocracy is

for the most part rather superficial. More often than not, it actually served to

mask deeper asymmetries and social hierarchies. Even though "cosmopolitanism and

natural equality are the obligatory themes of all the harangues of the Lodges,"

the European Lodges were usually far from "democratic," but were predominantly

aristocratic and highly elitist organizations.

Fraternal binding also obscured the social divisions and

inequities of rank endemic to the lives of men who embraced "equality" and

"liberty." In making social divisions less obvious freemasonry ironically served

to reinforce them. . . . They obfuscated the real divisions of wealth, education

and social practice (Jacob: 45).

[31] As Dumenil points out in the case of American

Masonry, even though the Masons insist on their universality and tolerance of

all classes, the Lodges were a predominantly white, middle class, Protestant

male phenomenon. Unlike many working class fraternal orders, the Masonic Lodges

drew an estimated 75 percent of their membership from white-collar workers. In

fact, the various dues demanded of the Masons were generally far beyond the

financial means of most blue collar men. In the Lodges which Dumenil studied,

for example, the initiation fees ranged from $50 to $100, with dues from $6-12

dollars; most blue collar workers at that time earned only about $570 annually,

meaning that few if any could afford membership.

Masons insisted that their order was committed to the principle

of universality, which they defined as the association of good men

without regard to religion, nationality or class. . . . Although Masonic

principles theoretically allowed for heterogeneity, the fraternity was

predominantly a white, native Protestant middle class organization (13).

Throughout Masonic rhetoric, moreover, we find a clear disdain for the

common, ordinary dullards - the "profane" - outside the sanctuary of the Lodge:

"Masons distinguish between the sacred world of Masonry and the external world

of the profanes . . . they contrasted the stability of their fraternity with the

disorder of American society" (Dumenil: xiii; Jacob: 123).

[32] As we see in the writings of Pike and many

other American Masons moreover, there is often a significant and rather

disturbing element of racism in the Lodge. Despite the fact that there were, by

the late nineteenth century, a number of Black Masonic orders, these were seldom

recognized as "legitimate" or authentic by the white Lodges. Even though Pike

himself had declared that "Freemasonry is one faith . . . around which men of

all tongues assemble," nevertheless, he also forcefully declared, "I took my

obligation to white men, not Negroes. When I have to accept Negroes as brethren

or leave Masonry I shall leave it" (cited in Whalen: 10). Although, as we have

seen, there is no evidence that Pike himself was ever formally involved with the

Ku Klux Klan, it is clear that he was in many ways sympathetic to the Klan's

agenda and its defense of traditional white Southern values (W. Brown 1997:

439ff). Throughout the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there

was often a disturbingly close relationship between the Lodge and the Klan:

after all, both groups shared common ideals of true Americanism and a common

suspicion of those racial and cultural groups - Negroes, Jews, immigrants - who

did not accept what they regarded as essential American values:

Although Masonry was less virulent in its Americanism campaign

than the Ku Klux Klan . . . both organizations shared some of the same goals.

Dismayed by all the factions disturbing America's harmony, both called for unity

in American life. But this unity . . . meant conformity to their vision of

American ideals, which included political and social dominance of their own kind

(Dumenil: 147).

Rather than opening their doors to men of all races and social classes,

creating an egalitarian utopian society, the Lodges were more often highly

exclusive clubs, the membership of which was carefully selected, and which

offered very clear avenues to achieving status, distinction, and social

connections: "membership carried tangible benefits. Businessmen made contacts,

cultivated credit sources, and gained access to a nationwide network of lodges.

Ambitious young men could socialize with their bosses" (Carnes 1989: 2).

[33] As I wish to argue , Pike and others became

interested in the rituals of Masonry as a means of resolving a number of

profound tensions faced by many affluent males of late nineteenth century

America - above all, the tension between the ideal of democracy and brotherhood,

on one the hand, and the wish to reinforce their own elite privileges, on the

other. The solution is to construct, within the esoteric space of the Lodge, an

alternative hierarchy of status, one which is ostensibly a "meritocracy." In

other words, a man gains status in the lodge, not because he comes from a good

family or has economic wealth, but because he is a "good man," a virtuous

individual who has proven himself through good works and character.

[34] In this way, the hierarchy of the Lodge not

only complemented but in many ways reinforced and reproduced existing

social and economic hierarchies. In Bourdieu's terms, we would say that the

rhetoric of "merit" serves to bestow a form of symbolic capital upon the Mason,

and this in turn legitimates deeper asymmetries of power and economic capital in

society. Elites in all cultures, Bourdieu suggests, must constantly exercise the

greatest "ingenuity to disguising the truth of economic acts" - that is, to make

their economic and political dominance appear to be based on something else,

such as merit, taste, or virtue. Through a kind of "social

alchemy "economic capital is made to appear "legitimate," becoming transformed

into "symbolic capital" by means of acts of charity, public displays of

generosity, patronage of the arts, etc. (1981: 114). Bourdieu describes a

similar process at work in the modern educational system. Whereas the

educational system purports to be a democratic system, a form of "meritocracy"

based on the progressive acquisition of valuable knowledge, it in fact

reinforces the power of the dominant classes. Providing the dominant classes

with a "theodicy of their own privilege," it transforms their economic capital

into a form of "cultural capital" - a degree, linguistic skills, a fluency in

art, and other cultural forms - which in turn justifies their status in the

social hierarchy, making it appear "legitimate" or "natural" (1981: 133). The

dominant class thus appears to be dominant, not simply because it possesses

economic capital, but because it possesses distinction, taste, and valued

knowledge:

The importance of institutionalized knowledge and

qualifications lies in social exclusion rather than . . . humanistic advance.

They legitimate and reproduce a class society. A seemingly democratic currency

has replaced real capital as the social arbiter in modern society. . . . It is

the exclusive "cultural capital" - knowledge and skill in the manipulation of

language - of the dominant groups which ensures . . . the reproduction of class

position. This is because educational advancement is controlled by the "fair"

meritocratic testing of precisely those skills which cultural capital provides

(Willis: 128).

In a similar way, I submit, the elaborate system of advancements in Scottish

Rite masonry functioned to bestow a kind of cultural capital upon the initiate,

a new status, and reputation as a virtuous, charitable, upstanding individual.

Under the appearance of a meritocratic system, it helped to legitimate and

naturalize the power of the dominant classes.

Symbolism and Secrecy: The Creation of Scarce Resources of Knowledge and

Power

Knowledge is the most genuine and real of human treasures; for

it is Light and Ignorance darkness. Secrecy is indispensable in a Mason of

whatever degree. It is the first . . . lesson taught to the Entered Apprentice

(Pike 1871: 107, 109).

The great secrecy observed by the initiated Priests . . . and

the lofty sciences which they professed, caused them to be honored and respected

throughout all Egypt. . . . The mystery which surrounded them strongly excited

curiosity (Pike 1871: 365).

[35] The primary mechanism for accumulating symbolic

capital within the Masonic tradition is through secrecy and esoteric symbolism.

Like the mysteries of the Greeks or the occult symbols of the Egyptians, Masonic

truths are too profound to be conveyed in plain literal language. Rather, they

must be transmitted through obscure, often seemingly nonsensical symbols and

enigmas, for there are "thoughts and ideas which no language ever spoken by man

has words to express." Moreover, secrecy and symbolism have been necessary to

preserve the most precious teachings from corruption by the institutional church

or tyrannical governments:

When despotism and superstition . . . reigned everywhere, it

invented, to avoid persecution, the mysteries, the symbol and the emblem and

transmitted the doctrines by secret initiation. Now it smiles at the puny

efforts of kings and popes to crush it (Pike 1871: 221).

Because they are so precious and so potentially dangerous, Pike warns, the

Masonic secrets must be reserved solely for those who are properly initiated.

One must be of the proper moral and intellectual calibre to be entrusted with

the possession of this awesome sacred knowledge. For those ignorant souls who

lack these qualifications, the elaborate symbols and hermetic interpretations of

Masonry are designed, not to lead them closer to the Truth, but, on the

contrary, to confuse, mislead, and misdirect them away from the innermost

secrets of the Craft:

Masonry, like all religions, all the Mysteries . . .

conceals its secrets from all except the Adepts and Sages or the Elect and

uses false explanations and misinterpretations of its symbols to mislead those

who deserve only to be misled; to conceal the Truth . . . from them and to draw

them away from it. . . . So Masonry jealously conceals its secrets and

intentionally leads conceited interpreters astray (Pike 1871: 104-5).

[36] Yet, despite these repeated warnings, it would

seem that the secret symbols of Masonry are, in themselves, really not

particularly shocking or remarkable; in fact, most of them would seem rather

mundane: "many people who take the oath would be hard pressed to define what

they are supposed to keep secret, unless it is simply the ritual steps, signs,

and passwords. These have long been accessible to any outsider who cares to do a

little research in a good library" (MacKenzie: 176). So why is it that they need

to be surrounded with such an enormous amount of secrecy, occultism, and

mystery? As I would argue, it is precisely all this secrecy and ritual ornament

- this "adornment of silence" - which functions to transform the otherwise

fairly mundane and unremarkable body of Masonic teachings into a rare, scarce

and highly valued commodity (see Barth: 217; Luhrmann: 161; Urban). They

create a precious resource, one which grows in value and buying power the

further one advances in the Lodge.

|

|

Figure 8

House of the Temple, Washington D.C. |

|

|

Figure 9

Scottish Rite Hall, Masonic Temple, San Francisco (Brockman: 39 |

|

|

Figure 10

Lodge with the Pillars Jachim and Boaz (MacNutly: 62) |

|

|

Figure 11

Mason Square |

[37] A complete analysis of all the various symbols

- not to mention all the levels of interpretation and hidden meaning - in Pike's

system would require a study at least as massive as the Morals and Dogma

itself. Let it suffice here simply to mention a few of the more important

symbols. The Lodge itself (figures 8 and 9) is a great Temple full of symbols,

patterned after the Temple of Solomon, which mirrors the great cosmic Temple of

God's universe; its two main pillars, called by the biblical names Jachim and

Boaz (figure 10), symbolize the primordial opposition of the positive and

negative forces of creation - male and female, light and darkness, sun and moon,

heaven and earth. For "every lodge is a temple, and as a whole symbolic. . . .

The arrangement of the Temple of Solomon, the symbolic ornaments which formed

its decorations, all had referents to the Order of the universe" (Pike 1871: 7).

Constructed of four hierarchical levels, the Lodge is then correlated with the

initial Masonic grades (the blue Grades of Tyler, Warden, Master, and the

Divinity above them), with the four dimensions of the cosmos (the physical,

psychic, heavenly, and divine worlds). As one ascends each of the initiations,

the secret symbols of the Masonic tradition are revealed in a progressive and

hierarchical order. At each grade, a new set of secrets is entrusted to him, and

it is largely the possession of this valued information - this cultural capital

- which defines the Mason's place within the hierarchy. In the first degree of

Apprentice, for example, the initiate is instructed in the meanings of the

Gavel, the Chisel, and the 24 inch Gauge, which represent the faculties of

passion, analysis, and measured choice; in the second degree, he is taught the

significance of the level, plumbline, and square (figure 11), which symbolize

respectively the standards of justice, mercy, and truth; finally, in the third

degree, he is taught the inner meaning of the compass, pencil, and skirrett,

representing his capacity for creativity, understanding, and balanced judgment.

Beyond these initial, rudimentary symbols, as one passes into the esoteric

grades of the Scottish Rite, the symbols multiply profusely. From his eclectic

readings of the world's sacred texts, Pike conceives an elaborate symbolic

tapestry, woven not only from the imagery of the Craft, but also from

alchemical, Kabbalistic and Templar lore (see Blanchard; Naudon: 235-36).

[38] Yet even though he devotes hundreds of pages to

elaborating their meaning, Pike repeatedly warns that the secret symbols of the

Lodge can never be reduced to a final interpretation. Indeed, their power lies

precisely in the fact that they transcend the limits of ordinary human thought.

These are secrets which "no language ever spoken by man has words to express."

Ultimately, the content of the symbols is not the most important

factor: what is important is the effect of the symbols on the initiate,

their affective power in generating awe, mystery and the sense of the

hidden power of the Masonic tradition. For "even if members failed to comprehend

the nuances of the rituals, the symbols evoked an appropriate feeling"

(Pike 1871: 22; cf. Carnes 1989: 35). As I would argue, what is important about

secrets is not primarily the occult knowledge they profess to contain, but

rather, the ways in which secrets are exchanged, the mechanisms of power

through which they are conferred, and above all, the kind of status and

"symbolic capital," which the possession of secret information bestows upon the

individual. The content is not, of course, entirely arbitrary or

meaningless, but its importance is secondary to its function as a source of

symbolic power. Pike himself seems to say as much when he describes the awesome

power of the "Grand Arcanum" - a secret so profound it cannot be expressed in

any form, a secret so dangerous it would destroy those who reveal it, a secret

so precious because it is the source of both knowledge and power:

[T]he Grand Arcanum [is] that secret whose revelation would

overturn Earth and Heaven. Let no one expect us to give them its explanation! He

who passes behind the veil that hides this mystery understands that it is in its

very nature inexplicable, and that it is death to those who win it by surprise

as well as to him who reveals it. This secret is the Royalty of the Sages, the

Crown of the Initiate (1871: 101).

[39] Not only are the numbers of symbols unlimited,

but the levels of interpretation, which become progressively more mysterious,

are equally endless. At each grade of initiation, in fact, the previous truths

of the earlier grades are stripped away, shown to be limited, relative,

teachings for the immature, while the deeper truth lies beyond. Pursuit of

knowledge becomes like peeling the layers of an onion, or exploring a set of

Chinese boxes: information on one level is the deceitful cover that creates

another kind of truth at a deeper level (see Barth: 82). The truth, Pike

suggests, is so easily profaned that it must be intentionally obfuscated or

concealed from low-level initiates, and reserved solely for the better prepared

adepts.

The Blue Degrees are but the outer court of the Temple. Part of

the symbols are displayed to the initiate, but he is intentionally misled by

false interpretations. It is not intended that he shall understand them, but

that he shall imagine he understands them. Their true explication it reserved

for the Adepts (1871: 819; my emphasis).

Indeed, even at the penultimate, thirty-second grade of the Sublime Secret,

the candidate is not actually told the deepest, innermost meaning of Masonic

symbols; rather, he is instructed that many symbols had still deeper meanings

and ties to ancient mysteries, but that he had "succeeded in obtaining but a few

hints" and could "communicate no more to you" (Blanchard: 438).

[40] In short, this system of progressive unveiling,

this peeling of the layers of secrecy, insures that the power and symbolic value

of the secret as a precious commodity always remains in tact. It remains a

source of mystery and a scarce resource, precisely because the Mason can never

know its final meaning, but must continue ascending grades of initiation, ever

uncovering deeper levels of truth. "Symbolism tended continually to become more

complicated; all the powers of Heaven were reproduced on earth, until a web of

fiction and allegory was woven . . . which the wit of man . . . will never

unravel" (Pike 1871: 63). Hence esoteric knowledge always remains a

valuable commodity, and, like all capital, the symbolic capital produced by

the possession of this commodity continues to grow and reproduce as one ascends

in rank and status.

Initiation, Hierarchy, and Status: Ascending Grades of Secrecy and Power

The fact that a man was connected with the Institution ought to

be a passport into any respectable society (The Trestleboard, 11 [May

1897]: 213-14).

Among men, some govern, others serve, capital commands and

labor obeys, and one race, superior in intellect, avails itself of the strong

muscles of another that is inferior (Pike 1871: 829)

|

|

Figure 12

Various Organizations and Degrees that Comprise Freemasonry (Brockman: 14) |

|

|

Figure 13

Initiatory Death (MacNulty: 81) |

|

|

Figure 14

Third Degree Tracing Board (MacNulty: 49) |

[41] The third strategy I wish to examine is the

construction of an initiatic hierarchy, a graded structure of ranks, which the

Mason ascends as he rises in esoteric knowledge. By being initiated into the

Masonic secrets, the novice gains a new identity, which is inscribed as a

subordinate limb within the hierarchical body of the Lodge ("Power in our Rite

descends from the summit," as Pike put it [Letter March 11, 1866, in W.

Brown 1997: 423]). Yet at the same time, this hierarchy also becomes a "ladder

of symbolic capital," a means to upward mobility which confers increasing status

and power upon the Mason (see Moore: 31-32; Clawson 1996: 53-54).

[42] The Scottish Rite is the most elaborate and

complex of all Masonic traditions. Whereas most Masonic orders have just three

grades - the Blue grades of Apprentice, Fellow, and Master - the Scottish Rite

adds an additional thirty, increasingly more mysterious levels of initiation

(figure 12). The first three grades, as we have seen above, contain the more

basic teachings of morality, loyalty, and obedience, as the novice is taught the

meaning of key Masonic symbols and the symbolism of architecture. The third

level of Master involves the important initiatory process of death and rebirth

(figures 13 and 14), whereby the Mason dies to his old identity in the exoteric

world and is reborn into a new identity within the Lodge. The brothers reenact

the legendary narrative of Hiram Abiff - the architect who knew the secret of

Solomon's temple and was killed by assassins for the sake of his knowledge. In

the process, the initiate himself undergoes a symbolic death and rebirth, now

grafted as a limb onto the greater hierarchical body of the Lodge (see

Blanchard: 438ff).

[43] Once he passes beyond the first three lower

grades, having undergone this death and rebirth into a new identity, the Mason

enters into the more elaborate hierarchy of the thirty higher grades. These more

secret initiations are conceived on the model of an intricate architectonic

structure, a great pyramid of increasingly prestigious ranks. We need not

analyze all thirty of these here - which begin with the grade of Secret Master

and extend to the highest, most powerful grades of Grand Inspector, Inquisitor

Commander, the Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret, and Sovereign Grand

Commander. What is important to note is, first, that these progressively

esoteric grades create a complex "map" or structural model of the ideal social

order, an order based on ever more esoteric degrees of knowledge, and ever

increasing levels of status (Moore: 31ff). At the grade of the Sublime Secret,

for example, the Commander leads the candidate to the west end of the lodge,

where a series of complex geometric figures are drawn upon the floor. First,

there is a nonagon, around which the other members stand, which is said to be

"symbolic of an encampment of the Masonic army." Having been informed that he

will now learn the most esoteric meaning of the order, the candidate then

circumambulates the nonagon twice. The figure is surrounded by a series of nine

flags, and at each flag, the Commander explains the meaning of the first

eighteen grades. He then reveals to the candidate a drawing of a nonagon, within

which are inscribed several smaller geometric figures - a septagon, which

symbolizes the nineteenth through twenty-fifth degrees; a pentagon which refers

to the twenty-sixth through thirtieth degrees, and within the pentagon there is

a triangle, then a circle and finally, at the very center of it all, a single

point. These last three figures refer to the three highest Masonic grades - the

Grand Inquisitor Commander, the Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret, and finally

at the center of all, the Sovereign Grand Commander. In this way, the entire

hierarchy of the Lodge is imaginatively constructed as a great pyramid or a

series of concentric geometric figures, mirroring the architectonic structure of

God's universe. Just as the entire cosmos ascends as a hierarchical structure,

rising from its base in the material world to the supreme point of Divine Unity,

so too, the Lodge ascends from its base in the common mass of mankind all the

way to the most elite, most sublime point of unity, the Sovereign Grand

Commander (Pike 1871: 7-8, cited above).

[44] As Bourdieu, Lincoln, and others point out,

symbolic maps and hierarchical schemas like this are very often also maps of

social space: they provide structural blueprints of a particular social and

political arrangement, making that arrangement appear to be "natural," as if

inscribed into the very structure of creation by the hand of the Divine

Architect. In short, "symbolic space (e.g. house, temple, ) is model of social

space (social, economic, and political hierarchies)" (Bourdieu 1977a: 89). In

fact, these kinds of symbolic hierarchies often serve to mask and recode social

hierarchies, making them appear "legitimate": by creating homologies and secret

correspondences between social, cosmic, and psycho-physical levels of existence,

they "provide an ideological mystification for sociopolitical realities," such

that "arbitrary social hierarchies are represented as if given by nature"

(Lincoln: 139-41).

[45] Finally and most importantly, however,

the elaborate grades of this initiatic hierarchy serve not only to create a kind

of social map, they also create a ladder of symbolic capital, a means to

achieving new status, power, and prestige within the Masonic community. As

Dumenil suggests, one of the primary reasons for the enormous popularity of the

Lodge in late nineteenth century America was that it offered young men a

powerful source of status and distinction: By creating an "elite group offering

prestige by advancements through the degrees," it served to "confer status on a

small number" and also offered a means to "financial aid, business and political

connections, and sociability."

[F]raternal orders provide average men with avenues for

achieving distinction. One major vehicle for attaining prestige within masonry

was office-holding. Masonry had a complex system of government staffed by

numerous officials. . . . [A] Mason would progress through the offices of

Steward, Junior Deacon, Senior Deacon, Junior Warden, and Senior Warden to

become Master (14; cf. Clawson 1996: 52).

As such, Carnes suggests, the elaborate ranks and promotions in the Scottish

Rite were especially attractive to socially ambitious men during an era of rapid

economic change:

Preoccupied with issues of status in a changing society, these

ambitious and politically active men did not intend to throw the doors of the

lodges open to all comers, but conceived of the order as a means of validating

their own attainments (1987: 22-23).

|

|

Figure 15

Rebis or Androgyne (Pike 1871: frontpiece, chap. 32) |

[46] Ultimately, at the highest level of initiation,

the Mason comes to learn the most profound, most secret essence of the

Brotherhood, which is at the same time the most prestigious of achievements:

this is embodied in what Pike cryptically calls the "Mystery of Balance" or

coincidence of opposites. Pike takes this mystery from the traditions of alchemy

and Kabbalah, and, in fact, the frontispiece of chapter thirty-two of Morals

and Dogma is a famous alchemical engraving of the Rebis or Androgyne (figure

15), borrowed from Basil Valentine. This is what the Kabbalist treatise, the

Zohar, describes as the secret of universal equilibrium between good and evil,

light and darkness. All contraries emanate from a single God. Male and female,

sun and moon, light and dark - symbolized by the Masonic compass and square, and

by the two pillars Jachim and Boaz - all come from the same source, and all

re-unite in the highest initiation. Pike believes that this most profound

mystery can be discovered by using the Kabbalistic technique of letter

combination, by taking apart and reforming the letters of the tetragrammaton,

the holy Name of God, YHWH. If the tetragrammaton is divided and read backwards,

it produces the word HO-HI. In Hebrew HO is the masculine pronoun, HI the

feminine. The reordered tetragrammaton is then translated as HE-SHE, which Pike

believes to be a confirmation that God is, in his ultimate essence, the bisexual

coincidence of opposites:

Reversing the letters of the Ineffable Name, and dividing it,

it becomes bi-sexual, as the word Yud-He or Jah and discloses the meaning of the

obscure language of the Kabbalah. . . . God created man as male and female (Pike

1871: 849).

[47] Carnes would like to give this esoteric

teaching a kind of psychological/gender interpretation: it affirms, he suggests,

the secret fact that men too have a feminine side, something which few Victorian

American males could admit publicly (1989: 149-50). However, I would argue for a

more social and political interpretation. Pike himself suggests that the true

meaning of this union of opposites is really the harmonious wedding of

individual freedom with hierarchical authority, the wedding of self-will with

obedience to law, which is the basis of the ideal social order. It is the

subordination of individual appetite - the human in us - to Reason and Moral

Judgment - the Divine in us, which is embodied in the Lodge. This hierarchical

union is the foundation of Freemasonry and the means to achieving the true "Holy

Empire," of which the Lodge is the model and prefiguration: "FREEMASONRY is

the subjugation of the Human that is in man by the Divine. . . . That

victory . . . is the true HOLY EMPIRE. Such is the true Royal Secret, which

makes possible, and shall at length make real, the HOLY EMPIRE of Masonic

Brotherhood" (Pike 1871: 855, 861). On the social and political level, this is

the union of individual free will and obedience to hierarchical power, which is

the foundation of the ideal Society and the truly just Government:

[T]he Equilibrium between Authority and individual action

constitutes Free Government by settling on . . . liberty with obedience to law,

equality with subjection to authority, Fraternity with subordination to the

Wisest and the Best (Pike 1871: 827).

[48] Here we find the final resolution of the deep

tension running throughout the American Masonic tradition - namely the emphasis

on freedom, equality, and individual sovereignty, on one hand, and elitism,

hierarchy, and subordination to higher authority, on the other. On one hand,

this supreme degree represents a powerful affirmation of the ultimate

sovereignty and freedom of the individual conscience. "We respect the creeds of

all men, because God alone is the supreme judge of his children. Each of our

Brethren has the right to . . . worship according to the dictates of his own

conscience" (Pike, in Whalen: 65). But at the same time, even while it affirms

individual freedom, it also reinforces a hierarchy of power based on reverence

for rank and the pursuit of status - the so-called "meritocracy" we have

analyzed above.

[49] Ultimately, Pike suggests, this is none other

than the natural law at work in all of creation, the subordination of the lesser

to the greater, the weak to the strong, the poor to the wealthy, which has been

ordained by God in nature and in the just society. Class hierarchies, labor

relations, even racial domination and slavery - all of these are

established by the will of God, and it is the duty of the true Mason freely to

obey them. As Pike explains in one particularly shocking and, to a contemporary

reader, quite offensive, passage:

The law of Justice is as universal as the law of Attraction. .

. . Among bees, one rules while the other obeys, some work while others are

idle. . . . The lion devours the antelope that has as good a right to life as

he. Among men, some govern, others serve, capital commands and labor obeys, and

one race, superior in intellect, avails itself of the strong muscles of

another that is inferior; and yet, no one impeaches the Justice of God. . .

. It is easy for some dreaming theorist to say that it is unjust for the lion to

devour the deer... but we know no other way . . . in which the lion could live .

. . [God's] justice does not require us to relieve the hardship of millions

of all labor, to emancipate the slave, unfitted to be free, from all

control (1871: 829; my emphasis).

Thus the secret truth of the highest degree is also the secret to reconciling

the ideals of freedom and equality with the desire for symbolic capital; it

offers a means of harmonizing democracy with the pursuit of status in an

asymmetrical hierarchy of ranks and degrees, based on a clear ideology of

exclusivism, classism, and racism.

Conclusions and Comparative Comments

The vagueness of symbolism, capable of many interpretations,

reached what the . . . conventional creed could not. Its indefiniteness

acknowledged the abstruseness of the subject; it treated the mysteries

mystically (Pike 1871: 22).

[50] By the second quarter of the twentieth century,

the Lodges appear to have lost much of the dominant role they had played in late

nineteenth century America. According to some like Dumenil, this was due to the

increasingly secular character of modern American culture, which made the

religious aspects of the rituals appear to be outdated and archaic. "The somber

religious tone of its ceremonies placed Masonry out of step with modern times"

(163). Others suggest that the economic functions of the Lodge, as a site of

business connections and financial relations, were rendered obsolete amidst the

increasingly complex structures of industrial capitalism. And still others like

Carnes point to changing conceptions of manhood, suggesting that young men in

twentieth century America shared fewer of their fathers' anxieties about

masculinity, and so no longer needed the elaborate patriarchal ritual of the

Lodges (1989: 154ff).

[51] Yet, whatever may be the reasons for its

gradual decline in this century, the American Lodge did for a time provide a

kind of oasis, an ideal realm in which white, upper and middle class values

could be reinforced. For men like Albert Pike, the secret symbols and

hierarchical initiations offered a means of acquiring status amidst an

increasingly heterogeneous world. But more importantly, the layers of secrecy

also served to re-code and legitimate that status, making it appear to be based

on merit, character, and moral goodness.

[52] Finally, I would also like to suggest that this

alternative approach to secrecy and this model of "adornment" could also have

much broader comparative implications for the study of esoteric traditions

cross-culturally. As I have argued here, secrecy is a strategy which may be